Table of Contents

Introduction

This article attempts to capture the methodology and rationale behind the social distance (SD) activities published by 205 Sports over the last few months. SD activities can serve a useful purpose in the development process even after removing COVID restrictions – as an initial phase in a session or as a standalone activity to teach tactical awareness and principles.

We describe a philosophy of developing SD activities – starting with a well-known game – and discuss how the principles within the activity relate to the “real” game. SD provides an opportunity for creativity and deeper learning for ourselves and our players.

Background

In late 2019, we began publishing practice activities (opposed and unopposed, rondos, positional play, small-sided games) on the 205 Sports Twitter feed. Each activity consists of a short (45-90 sec) video using a combination of TacticalPad, SnagIt, and Camtasia. The intent is to tell a short story within the video, using movement and stoppages, annotation, and diagrams. The target audience of the videos is youth (U9-U15) coaches.

COVID shut down field-based activities during Mar-Jun 2020 in Northern California. 205 Sports has been publishing “At-Home” practice plans for players who cannot participate in team sessions – individual technical and physical development. In early Jul 2020, we were once again allowed in Northern California to hold field-based sessions within strict US Soccer phase 1 guidelines. As of this publication (mid-Aug 2020), there is no timeline for entry into later phases, which would allow physical contact between players.

In response to the phase 1 restrictions, we shifted gears in Jun 2020 to publish TacticalPad activities using social distancing rules – to serve the audience of coaches that want to hold sessions but are required to conform to the conditions imposed in phase 1. These sessions have been provided to a local soccer club (UC Premier) and integrated into their field-based training.

Model

The one constant rule in developing SD activities is that players must perform all actions at a minimum of 6 feet (2m) apart. The implication is that every player must be assigned to a particular space at any moment in the activity, and only one player can be in the space. Players may not physically challenge each other.

However, it should be noted that players can be allowed to exchange places or to move between different spaces as long as the distance rule is maintained.

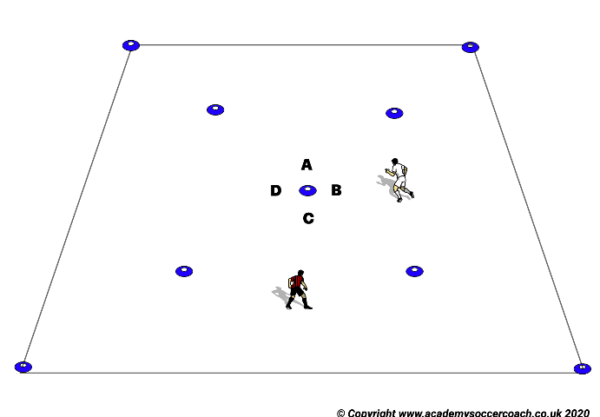

Consider this picture:

The grid is divided into four triangles (zones) – A, B, C, D. The White player is in B, the Red player is in C. The White player may not move into C while the Red player is there – nor can the Red player move into B while the White player is there.

If the White player moves into A, the Red player can move into either B or D. Each player must scan the field and determine the other player’s location when deciding whether the act of moving into a triangle is or is not allowed.

So, a common attribute of SD activities is an explicit definition of the zones on the field. These zones need to be marked – using cones, dots, or (if available) lines.

On reflection, this is a significant challenge in creating and executing an SD activity and can limit the number of players. In a 6v6 SD game, there must be a minimum of 12 separate zones – more if the players are allowed to transit between zones. Laying out cones and describing the rules associated with the zones can be time-consuming. If there are too many zones and rules, it is confusing for the players and is unlikely to meet the coach’s objectives. Coaches must consider the intellectual maturity of the players and the complexity of the rules as part of session design.

Theoretical foundation

Renshaw et al. (2019) provided a deep dive into the constraints-led approach (CLA), a model of practice design based on manipulating the environment to support learning affordances. CLA introduces a four-step model (GROW) to frame the planning process:

- Goal – what do you want, what’s the goal for the session, how does it link to the overall goal, what is the focus for learning

- Reality – where are you now, what’s the current skill level (coordination, adaptability), what affordances of the performance environment do you want to design into the practice (which, why, when)

- Option – what could you do, what practice activities will bridge the gap, what practice environment will you use, how will you measure performance

- Way forward – what will you do, how will you prepare the practice environment, how will you prepare the performers for the session, is there anything else you need to do to be ready

It is worth considering each of these steps when creating an SD activity – in particular, how the definition of zones and player movements provides affordances for the participants.

Relatedness to the real game - principles

When developing an SD game, a primary goal should be creating a scenario that has a relationship to the real game – and the principles underlying the game – that can be understood and expressed by the players. Developing an activity that requires the players to assume static positions or does not integrate scanning and decision making or limits choices or does not include some element of pressure results in players learning poor habits or the wrong lessons.

In addition to the zone constraints, it may be necessary to add additional rules (for example, touch or time limits) to create pressure.

An observation when performing SD activities is that players may choose to stand in one spot within their zone, knowing that no other player can occupy the zone. The coach’s response should be to encourage the kinds of movement within the zone that would mimic “real game” behavior. The addition of a “dead space” within the zone that the player must work around (for example, a cone or cones to mimic a defender) can provide an additional visual cue.

An example - the river game

Adopting an activity already known by the players and coach to SD simplifies the learning process. The players are already familiar with the basic ideas and cues, and the coach is familiar with how to present and manage the activity.

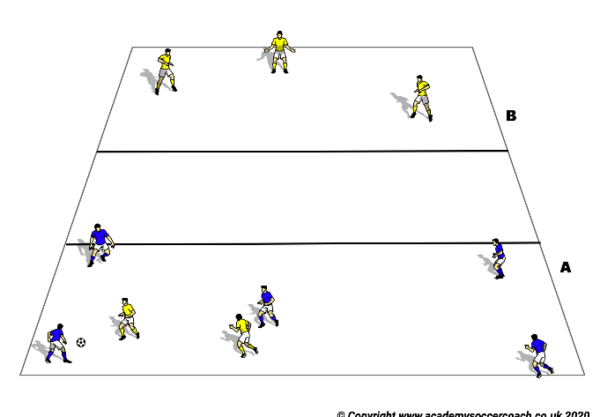

Here is how the river game can be turned into an SD activity. The river game involves dividing a grid into three zones:

The game starts 5v2 in one grid with the three teammates of the defenders in the other grid. No play occurs in the middle grid. Blue attempts to keep away from Yellow. If Yellow wins the ball, they will play across the central grid to their teammates and join along with two Blue players to form a 5v2 in the other grid. A typical game involves scoring points for a certain number of passes in a row. The decision as to which two players become defenders when the ball is switched is made on-the-fly by the players.

From an SD standpoint, two problems have to be addressed:

- There is no social distancing between teammates and opponents in the 5v2.

- When the ball transitions between sides, four players (2 from each team) move between the grids without any SD.

The first problem can be solved by assigning zones to each player. The question is how to create zones in a manner that reflects a consistent theory of the game.

After taking part in the TOVO V1 Online Course in 2019, we have adopted their principles and methodologies as part of our player development foundation. TOVO expresses a clean model – manage oneself, manage the ball, manage space – that can be communicated to players and integrated into activities.

In the river game, we envision a picture in which the attacking players manage space through the identification and execution of rondos within the grid. Movement of the ball between zones is facilitated through a central midfielder (the “6”). The defenders must be positioned to create some challenges to the attackers and respond to the ball’s movement in a game-like manner.

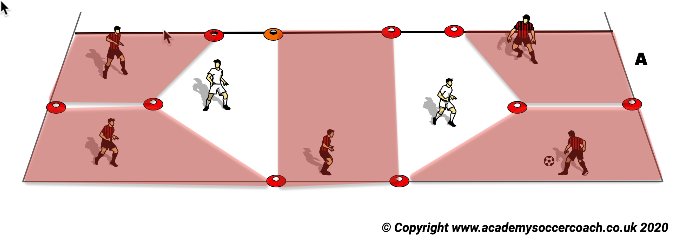

After consideration, we arrived at this picture:

Although the “wing” players can pass between their grids in an uncontested manner, any pass through the middle can be challenged. Each side of the grid is effectively a 3v1 rondo. The central player acts as a connector between the wings.

This leaves the second problem – the transition between grids. We must create a situation where players moving from one grid to the other are not occupying the same 6 feet (2m) area.

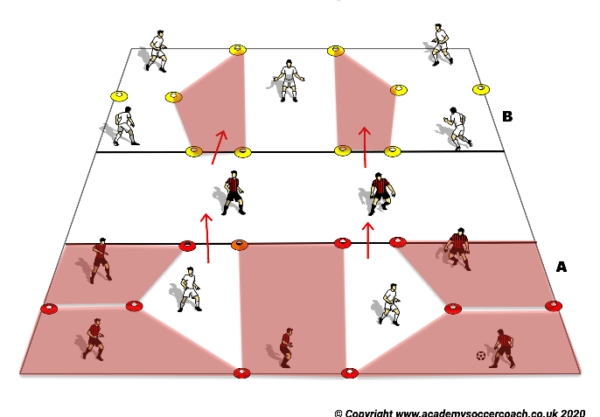

The solution is to add two Red players in the central grid who move into the opposite grid with the ball. Once the Red players have moved into the opposite grid, the White players formerly in the 5v2 grid move to the middle:

Here is the complete picture:

When the ball moves from grid A to grid B, the two White players in grid A may only move to the central grid once the Red players in the central grid move into B. This maintains the SD rules.

Here is the video version of the activity:

Applicability to the real game

Many consider the use of SD activities as a stopgap in place of having “real” activities. In short, “we do it this way because we have to, not because we want to.”

However, let’s consider the SD river game and what it can teach our players for the real game.

Having used the regular river game with teams of various ages, I’ve often observed that the attacking players either bunch up or stand in one place or do both. Defenders win the ball either due to poor passes or poor positioning of the attackers.

In the SD version, we have laid out a positioning of the attackers that provides a game-like spacing. We see two triangles, one on each side of the grid. The central attacker facilitates side-to-side movement of the ball. Our two defenders are forced to make choices in terms of pressure or cover and must be aware of the spaces behind them and the movement of opponents. All of these behaviors reflect the challenges that our players would observe in the game.

On the transition, the defenders (White in our example above) must scan the positioning of the central grid defenders to determine how to pass through their line, and the White teammates must move to create the passing windows. On the actual transition into the middle grid, the White players must observe the movement of the Red players to time their runs forward.

One can conclude that the SD river game can be a good starting point to work with players on spacing, movement, and transition. A progression that leaves the cones in place as a visual cue but removes the zone rules can support the learning process.

In summary, the use of SD zones and rules can accelerate the tactical development of players within a well-known activity.

Notably, as a coach, the challenge of creating SD activities out of existing activities requires a more profound thought process on principles and teaching methods. One must answer the question of purpose when adopting an activity for SD.

With creativity, we can design SD activities that reflect game principles within distancing constraints. Modification of the activity can increase challenges for the players and provide new learning opportunities.

References

Renshaw, I., Davids, K., Newcombe, D., & Roberts, W. (2019). The constraints-led approach: Principles for sports coaching and practice design. Routledge.